From Horses to Handguns: Captain W.E. Fairbairn and the Birth of Modern Practical Shooting

A Weapon Born in the Saddle

The pistol was not born as a badge of civilian carry or a soldier’s sidearm. Its first design was utilitarian: a one-hand gunfor cavalrymen. One hand controlled the reins of a horse; the other fired the weapon. The stance of the mounted shooter — upright torso, extended arm — carried forward into the first manuals on handgun use.

Even after horses were replaced by machines, the pistol survived. Its compact size, carry convenience, and concealability ensured it remained relevant in both military and civilian life. But while technology advanced — revolvers giving way to semi-automatics like the Colt 1911 — the techniques of using them stagnated. Men continued to mimic cavalry posture, simply shooting from the ground instead of the saddle.

That changed with one man: Captain William Ewart Fairbairn.

“The pistol is not a target weapon. It is a weapon of combat.”

— Shooting to Live with the One-Hand Gun

The Shanghai Laboratory

To understand Fairbairn, you must first understand his environment. Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s was, by many accounts, the most dangerous city in the world. A volatile mix of organized crime, political unrest, and international intrigue turned its streets into a battleground.

Fairbairn served with the Shanghai Municipal Police, where his unit fought in over 200 armed encounters. Over the course of 12 years, he analyzed nearly 2,000 gunfights, personally participating in more than 200 of them.

Shanghai’s back alleys became his laboratory. He wasn’t theorizing from a lecture hall — he was learning under fire, recording what worked, and discarding what didn’t.

“We claim no originality for our system… What we have done is to gather together the methods which experience has shown to be the best.”

— Shooting to Live

Scientific & Data-Driven Training

Fairbairn approached combat like a scientist. He meticulously tracked distances, lighting conditions, hit probabilities, and human reactions under stress. From those records, he extracted universal lessons.

His conclusion was blunt: most gunfights happen at very close range, often in poor light, and under maximum stress. That fact shaped every method he taught.

“The majority of shooting affrays… take place at not more than four yards, very frequently at less.”

— Shooting to Live

Combat vs. Competition

At the time, most police and military shooting was built around precision target practice. Marksmen trained to stand still, aim carefully, and squeeze off perfect shots. Fairbairn dismissed this as irrelevant to real-world violence.

“Beyond helping to teach care in the handling of firearms, target shooting is of no value whatever in learning the use of the pistol as a weapon of combat. The two things are as different from each other as chalk from cheese.”

— Shooting to Live

Speed: The Quick and the Dead

Fairbairn’s most consistent theme was speed. He understood that in close-quarters gunfights, the first effective shot usually wins.

“If you take longer than a third of a second to fire your first shot, you will not be the one to tell the newspapers about it. It is literally a matter of the quick and the dead. Take your choice.”

— Shooting to Live

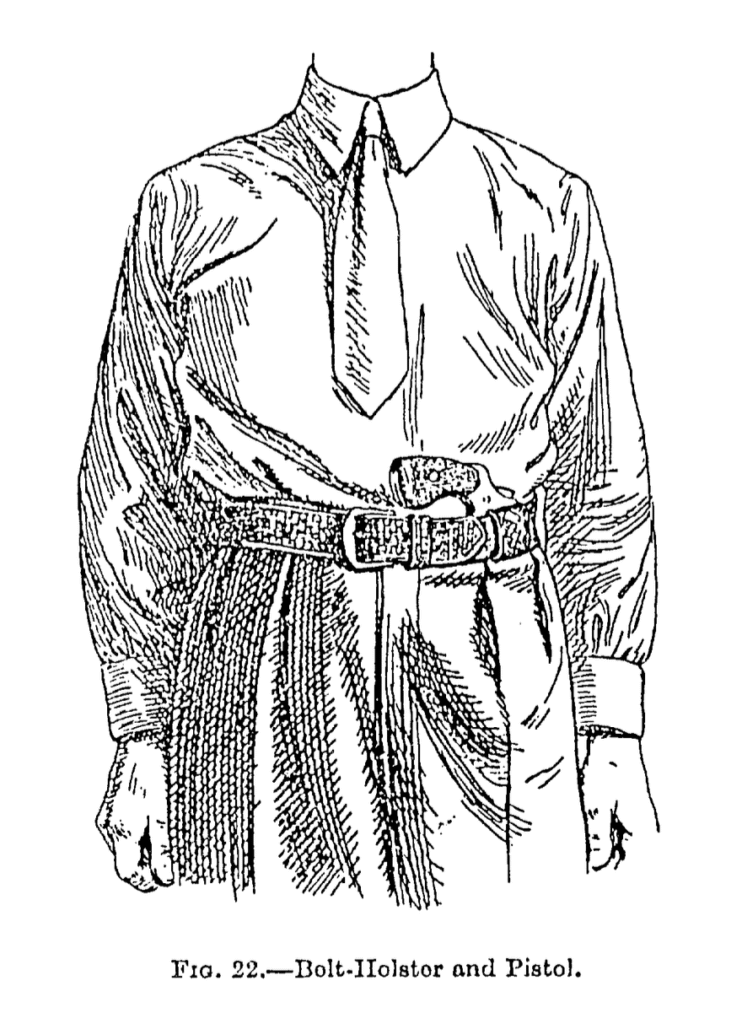

This wasn’t just rhetoric. Fairbairn trained recruits to draw and fire in a single, instinctive motion. He even went so far as to pin down safeties on pistols, reasoning that the delay they caused was more dangerous than the risk of accidental discharge.

Instinctive Aim

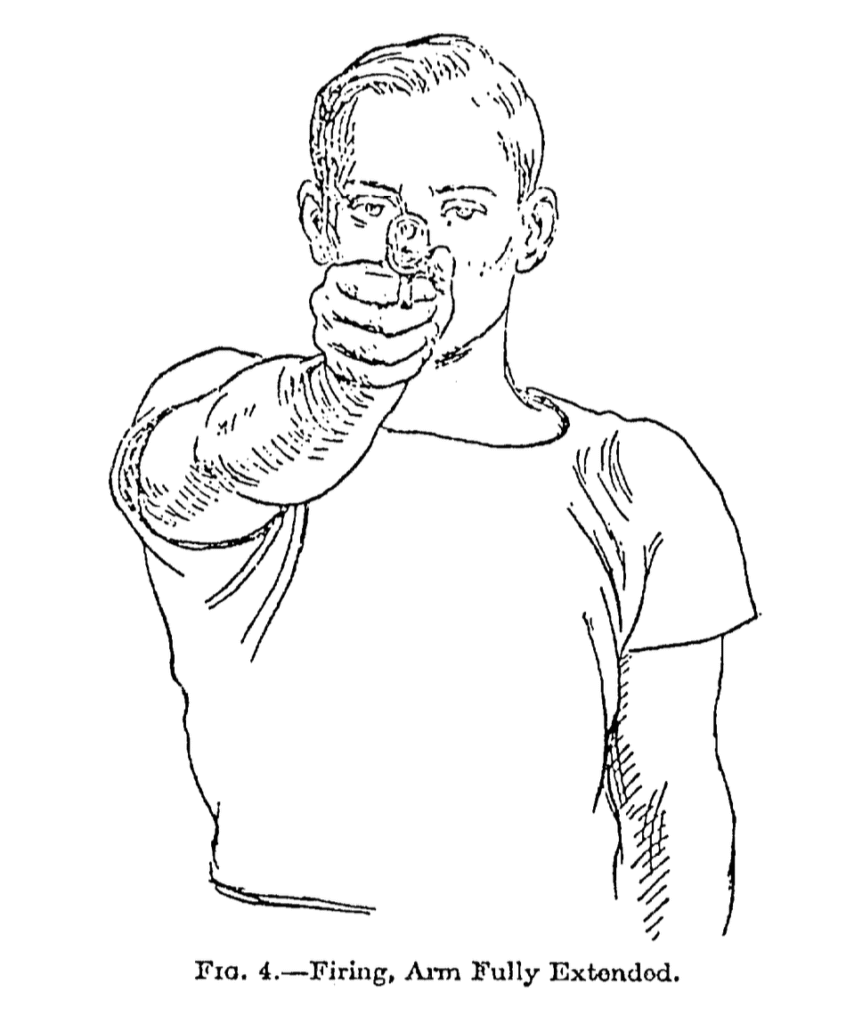

Fairbairn recognized the limits of traditional marksmanship in real fights. At four yards in dim light, there was no time for sight alignment. The answer was instinctive aiming — what today we might call point shooting or natural point of aim.

“Would it not be wiser, therefore, to face facts squarely and set to work to find out how best to develop instinctive aiming to the point of getting results under combat conditions?”

— Shooting to Live

Stance and the Crouch

One of Fairbairn’s most distinctive contributions was his advocacy of the “crouch” stance. Critics mocked it, but its origin was purely practical.

During a pre-dawn raid through a narrow alley in 1927, Fairbairn’s men later discovered wires stretched across at face level. None of the raiding party had struck them. In the darkness, under the expectation of enemy fire, every man had instinctively crouched.

Fairbairn drew the lesson: train men to fight as they would naturally react under stress.

“Since that time… men trained in the methods of this book have not only been permitted to crouch but encouraged to do so.”

— Shooting to Live

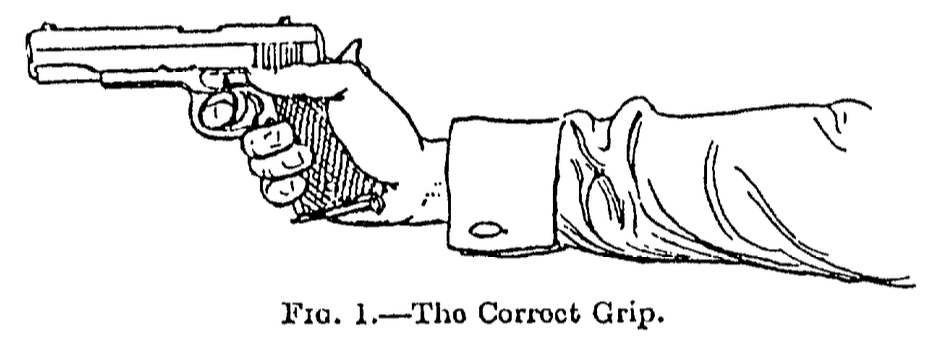

Grip and the Early Two-Handed Future

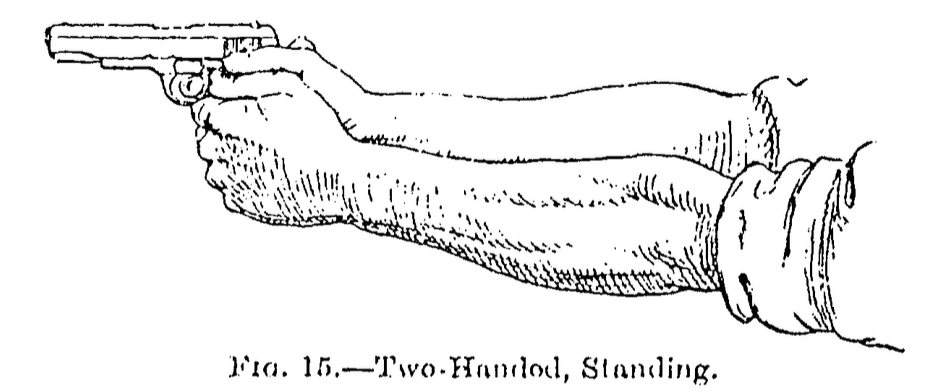

Fairbairn still viewed the pistol as a “one-hand gun,” faithful to its cavalry roots. But he acknowledged the value of two-handed shooting at longer ranges.

“The right arm is rigid and is supported by the left. Practice at any reasonable distance from 10 yards upwards.”

— Shooting to Live

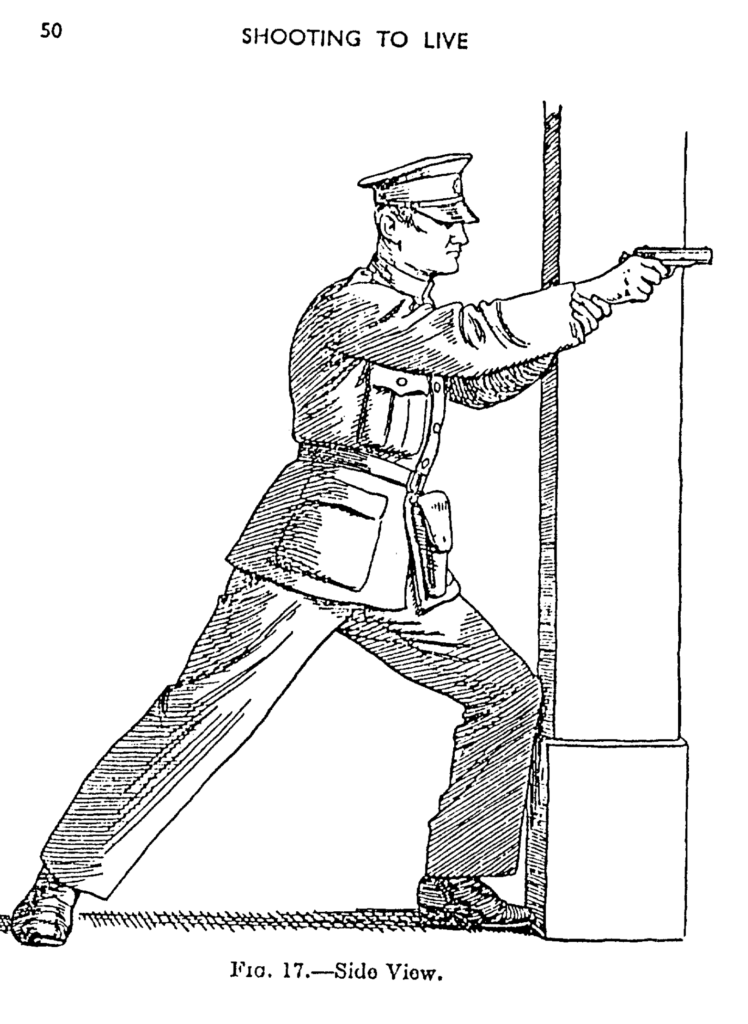

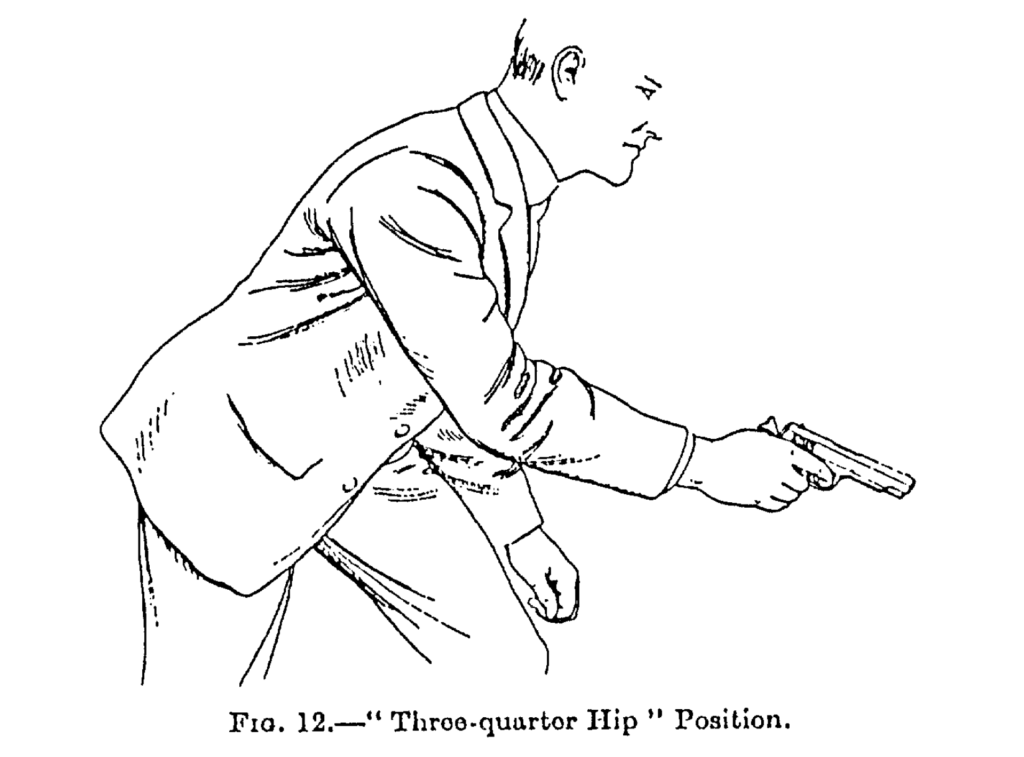

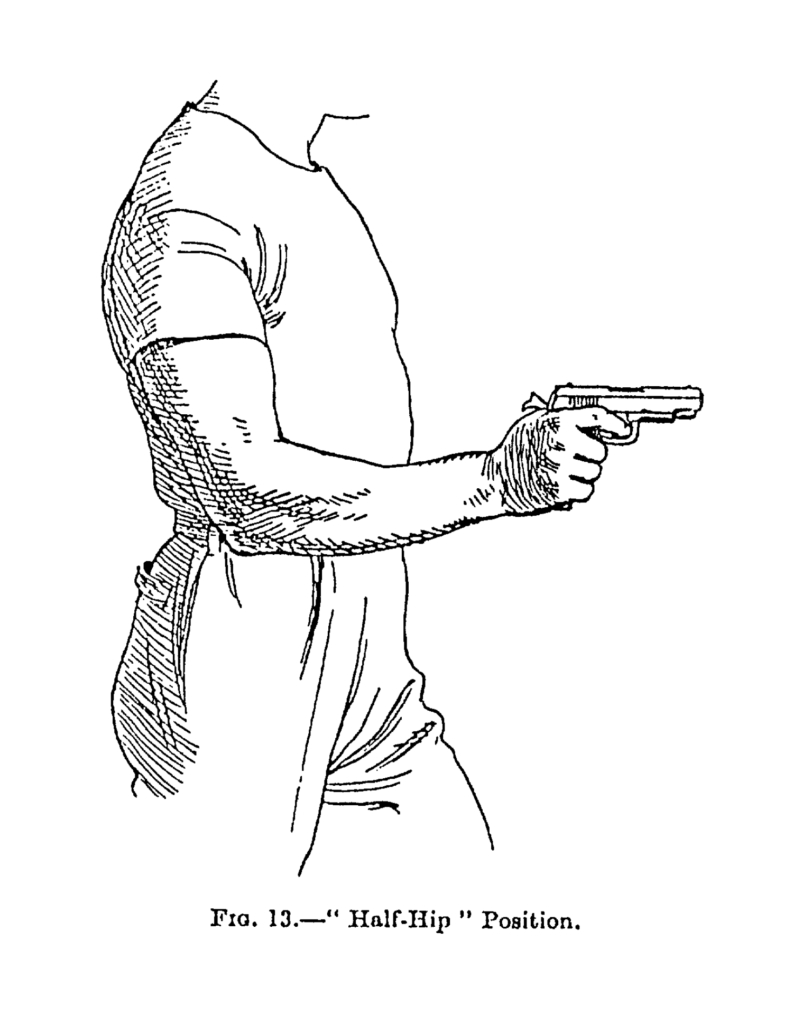

Positions, Cover, and Realism

Fairbairn insisted that recruits train in varied conditions: low light, awkward positions, bad weather, and while on the move. He understood that real gunfights are never clean.

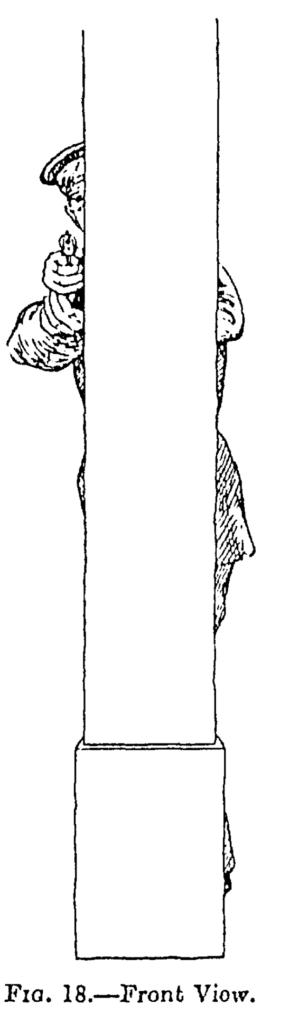

He also stressed the importance of using available cover, however improvised.

“Kind providence has endowed us all with a lively sense of self-preservation and some of us with a sense of strategy as well. If our readers are in the latter class we need not remind them of the advantages of taking cover whenever possible.”

— Shooting to Live

The Fore-Father of Modern Shooting and Training

Fairbairn’s influence reached far beyond Shanghai. His methods shaped British Commandos, the U.S. Marine Raiders, and the OSS during World War II. The men he trained carried his lessons into every corner of modern close-quarters combat doctrine.

While stances, grips, and technologies have evolved, his principles endure: train for reality, act with speed, and simplify to survive.

“We believe the methods which follow will save lives.”

— Shooting to Live

Standing on His Shoulders

At Strategic Defense Academy, we make no claim to pioneer these truths. Men like Captain W.E. Fairbairn paid for them in blood and experience. We are students of their legacy, standing on their shoulders, applying their lessons with modern tools and hard-won lessons of our own.

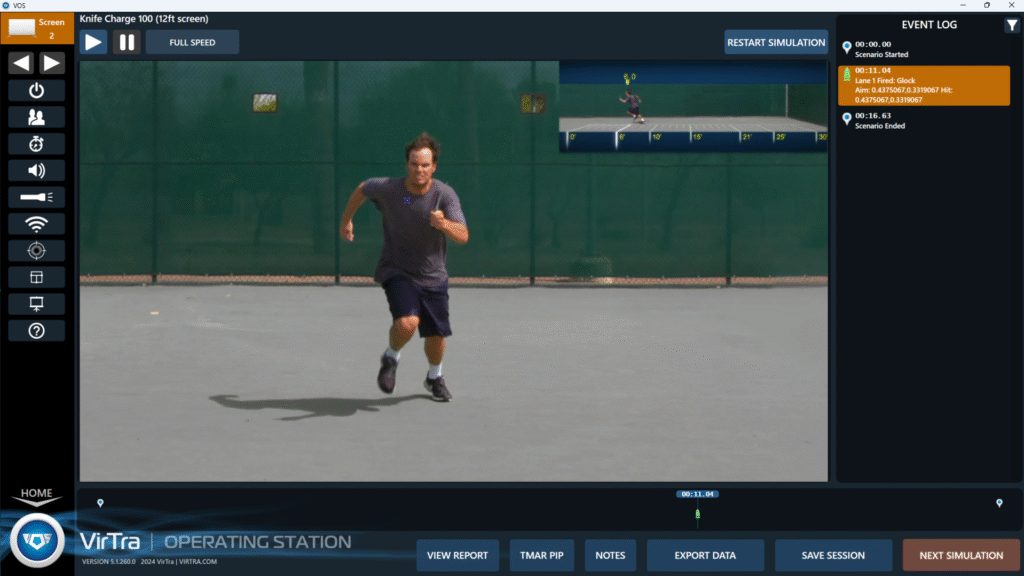

Where Fairbairn used Shanghai’s alleys, we bring together both lived experience from instructors who have faced violence firsthand and modern methods of analysis. We use body cameras, force-on-force simulations, and immersive simulators to study and refine what reality demands. Where he learned from street fights, we learn from both those who have been there and from the vast library of real-world footage, case studies, and post-incident reviews available today.

But the principles are the same:

Train for the real fight, not for the range.

Base instruction on reality and evidence, not tradition.

Prepare ordinary men and women to prevail under extraordinary pressure.

Fairbairn’s motto was simple: shoot to live.

Ours carries that spirit forward: Prepare. Protect. Prevail.