William E. Fairbairn, a former police officer in Shanghai during the tumultuous 1930s, found himself in a city ruled by ruthless gangs where “murder, rape, and robbery were the order of the day.” His experiences in this perilous environment would shape the future of combat shooting. In the words of Col. Rex Applegate,

“By actual records, …Fairbairn … with the Shanghai police engaged in over two hundred incidents where violent close combat occurred with oriental criminal elements. These battle-scarred veterans were experts in all types of close-quarter fighting with and without weapons. Their training techniques and methods were proven first in the back alleys of Shanghai and later with the Commando and Special Intelligence branches of both the British and U.S. services.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

In the crucible of these dangerous streets, Fairbairn learned valuable lessons about what worked and what didn’t. Over 12½ years, he meticulously analyzed approximately 2,000 gunfights, personally participating in over 200 of them.

Fairbairn was a pioneer in data-driven instruction, bringing a scientific approach to close-quarters pistol combat. Shanghai’s unforgiving streets served as his laboratory. His insights from these experiences remain invaluable to the field of practical pistol shooting.

Recognizing the shortcomings in existing pistol shooting manuals, he decided to create his own guide to combat pistol shooting.

Fairbairn’s perspective on target shooting was clear:

“Beyond helping to teach care in the handling of firearms, target shooting is of no value whatever in learning the use of the pistol as a weapon of combat. The two things are as different from each other as chalk from cheese.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

He emphasized that proficiency in combat conditions required an entirely different approach.

His experience taught him that speed was the decisive factor in life-or-death situations. Deliberate, precision shots that might be suitable for target shooting took too much time. In a gunfight, speed was paramount.

“At this point it would be advisable to examine very carefully the conditions under which we may expect the pistol to be used, regarding it only as a combat weapon. Personal experience will tend perhaps to make us regard these conditions primarily from the policeman’s point of view, but a great many of them must apply equally, we think, to military and other requirements in circumstances which preclude the use of a better weapon than the pistol that is to say, when it is impracticable to use a shot-gun, rifle or sub-machine gun.“

Fairbairn acknowledged the importance of the long gun over the pistol, using the latter only when the former was impractical. His insights were particularly relevant to close-quarter encounters, where most shootings occurred within four yards or less, often in poor lighting conditions and with little warning.

“In the great majority of shooting affrays the distance at which firing takes place is not more than four yards. Very frequently it is considerably less. Often the only warning of what is about to take place is a suspicious movement of an opponent’s hand. Again, your opponent is quite likely to be on the move. It may happen, too, that you have been running in order to overtake him. If you have had reason to believe that shooting is likely, you will be keyed-up to the highest pitch and will be grabbing your pistol with almost convulsive force. If have to fire, your instinct will be to do so as quickly as possible, and you will probably do it with a bent arm, possibly even from the level of the hip. The whole affair may take place in a bad light or none at all, and that is precisely the moment when the policeman, at any rate, is most likely to meet trouble, since darkness favors the activities of the criminal.

It may be that a bullet whizzes past you and that you will experience the momentary stupefaction which is due to the shock of the explosion at very short range of the shot just fired by your opponent a very different feeling, we can assure you, from that experienced when you are standing behind or alongside a pistol that is being fired. Finally, you may find that you have to shoot from some awkward position, not necessarily even while on your feet…Here we have a set of circumstances which in every respect are absolutely different from those encountered in target shooting. Do they not call for absolutely different methods of training?”

Gunfights were fast, often with opponents on the move, and stress running high. Fairbairn emphasized the need to train for such scenarios, including low-light and no-light conditions, as well as various shooting positions.

His key takeaways were simple yet profound:

- extreme speed in drawing and firing

- instinctive aim (point shooting)

- practice under conditions that resembled real combat.

Extreme Speed

“In commenting on the first essential, let us say that the necessity for speed is vital and can never be sufficiently emphasized. The average shooting affray is a matter of split seconds. If you take much longer than a third of a second to fire your first shot, you will not be the one to tell the newspapers about it. It is literally a matter of the quick and the dead. Take your choice.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

Fairbairn understood that in a split-second confrontation, speed was the difference between life and death. Training holster draw and point shooting was his method of increasing speed in recruits. He viewed the safety mechanism on a firearm was anything but safe.

“We have an inveterate dislike. of the profusion of safety devices with which all automatic pistols are regularly equipped. We believe them to be the cause of more accidents than anything else. There are too many instances on record of men being shot by accident either because the safety-catch was in the firing position when it ought not to have been or because it was in the safe position when that was the last thing to be desired. It is better, to think, to make the pistol permanently “unsafe” and then to devise such methods of handling it that there will be no accidents. One of the essentials of the instruction courses which follow is that the pistols used shall have their side safety-catches permnmently pinned clown in the firing or ‘unsafe’ position.”Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

In William E. Fairbairn’s era, revolvers and the 1911 were the primary choices for duty weapons, each having its own set of advantages and disadvantages concerning safety, the speed of the first shot, capacity, and follow-up shot speed. However, it wasn’t until the 1980s when Glock introduced a firearm that encompassed all the desired characteristics Fairbairn described in his book, notably the absence of a mechanical safety feature. This marked a significant evolution in firearm design and functionality.

Instinctive Aim

“Instinctive aiming, the second essential, is an entirely logical consequence of the extreme speed to from which we attach so much importance. That is so for the simple reason that there is no time for any of the customary aids to accuracy. If reliance on those aids has become habitual, so much the worse for you if you are shooting to live. There is no time, for instance, to put your self into some special stance or to align the sights of the pistol, and any attempt to do so places you at the mercy of a quicker opponent.“

“In any case, the sights would be of little use if the light were bad, and none at all if it were dark, as might easily happen. Would it not be wiser, therefore, to face facts squarely and set to work to find out how best to develop instinctive aiming to the point of getting results under combat conditions?”

“Before we close the subject of shooting at short ranges, we would ask tho reader to keep in mint that if he gots his shot off first, no matter whether it is a hit of is miss by a narrow margin, he will have an advantage of sometimes as much as two seconds over his opponent. The opponent will want time to recover his wits, and his shooting will not be as accurate as it might be.”Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

Fairbairn’s emphasis on the importance of taking the first shot is a timeless principle in combat. It aligns with the teachings found in Army Field Manual 7-8, which addresses reacting to contact. Additionally, this concept resonates with the work of Colonel Cooper on the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act), which underscores the critical role of initiative and speed in gaining the upper hand in any confrontation. Fairbairn’s wisdom highlights the psychological advantage gained by those who act decisively and swiftly in high-stress situations, a principle that remains relevant in modern combat training and tactics.

Stance Critical to Instinctive Shooting

“Tho instructor should make a special point of explaining all tho elements of this practice. The bent arm position is used because that would be instinctive at close quarters in a hurry. The square stance, with one foot forward, is precisely tho attitude in which tho recruit is most likely to be if ho had to fire suddenly while he was on the move. The “crouch,” besides being instinctive when expecting to be fired at, merits a little further explanation.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

The “crouch” position, mocked in modern times, had its roots in Fairbairn’s practical experience. He introduced it into his training system after an incident where his team had to navigate a narrow alley.

“It’s introduction into this training system originated from an incident which took place in 1927. A raiding party of fifteen men, operating before daybreak, had to force an entrance in to a house occupied by a gang of criminals. The only approach to the house was through a particularly narrow alley, and it was expected momentarily that the criminals would open fire. On returning down the alley in daylight after the raid was over, the men encountered, much to their surprise, a series of stout wires stretched at intervals across the alley at about face height.

Tho entire party had to duck to get under the wires, but no one had any recollection of either stooping under or running into them when approaching the house in tho darkness. Inquiries were made at once, only to reveal that the wires had been there over a week and that they were used for the wholly innocent purpose of hanging up newly dyed skins of wool to dry. The enquiries did not, therefore, confirm the suspicions that had been aroused, but they did serve to demonstrate conclusively and usefully that every single man of tho raiding party, when momentarily expecting to bo fired at, must have crouched considerably in the first swift traverse of the alley. Since that time, men trained in the methods of this book have not only been permitted to crouch but have been encouraged to do so.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

The crouching position proved instinctive when expecting gunfire and was adopted as a valuable tactic.

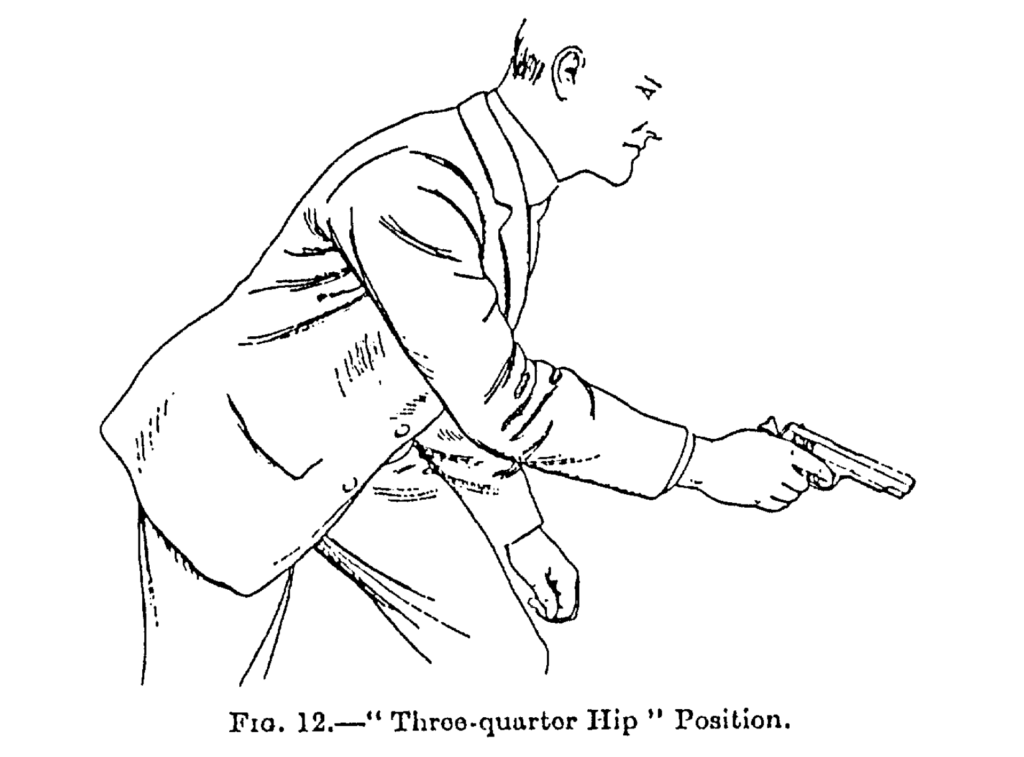

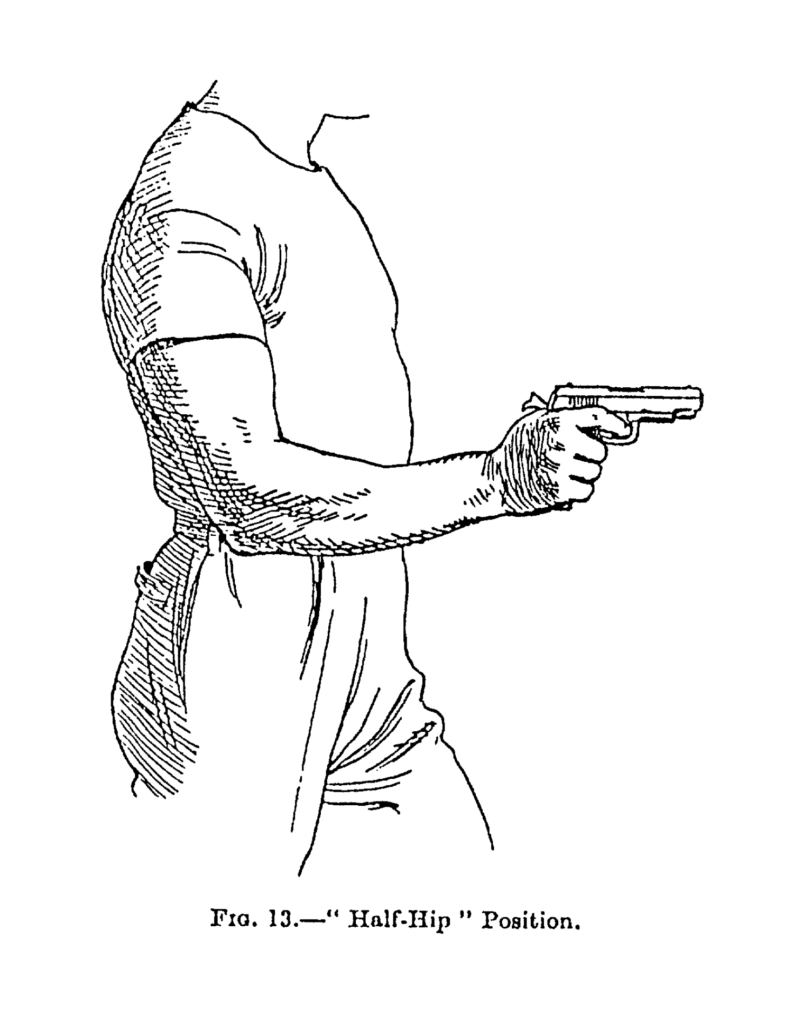

“Apart from shortening the arm by bringing the elbow to the side, the “half-hip” is no different from the “three-quarter” and should be practiced at not more then three yards. Above that distance it would be more natural to shoot from the “three-quarter” position.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

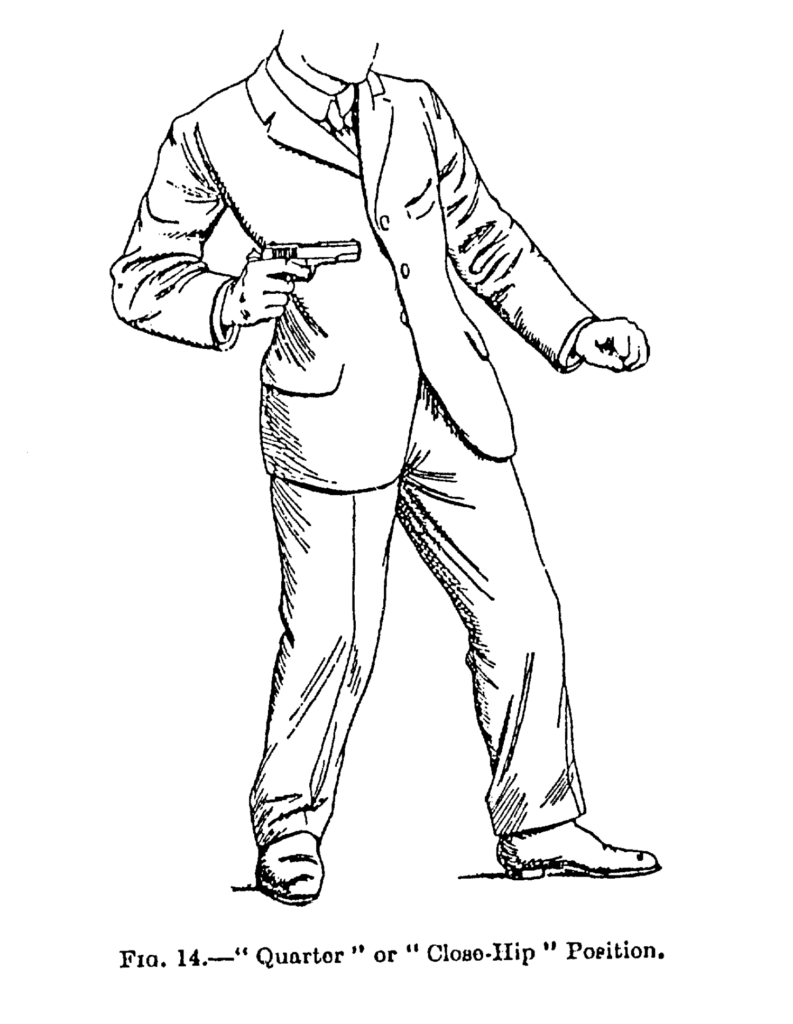

The “quarter” or “close-hip” position is for purely defensive purposes and would be used only when the requirements are a very quick draw, followed by in equally quick shot at extremely close quarters, such-as would be the case if a dangerous adversary were threatening to strike or grapple with you. Practice this at 1 yard. This is the only position in which the hand is not in the centre of the body.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

Over time, shooting stances have evolved quite a bit, favoring body alignment and upright heads-up posture, especially when equipped with body armor and helmets. However, Fairbairn’s contributions to close-quarters combat shooting remain foundational: Stance is critical to quick instinctive shooting.

Grip

The concept of firearm grip saw significant advancements in later years. While Fairbairn did cover grip techniques in his teachings, they remained relatively underdeveloped. His book’s subtitle, “with the one-hand gun,” reflects his perspective that the firearm was primarily designed for one-handed use, not two-handed. It’s worth noting that it’s called a “handgun” for a reason, not a “hands gun.” However, Fairbairn did acknowledge situations that necessitated two-handed shooting:

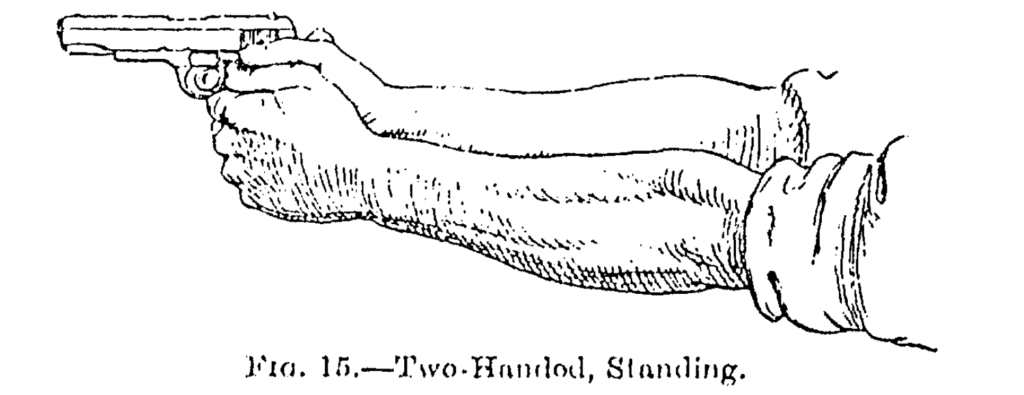

“The right arm is rigid and is supported by the left. Practice at any reasonable distance from 10 yards upwards.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

Fairbairn believed that using two hands on the “one-hand gun” was suitable for engaging targets at distances of 10 yards and beyond. His two-handed shooting technique, as depicted in Figure 15, aligns closely with the modern conventional wisdom of using a two-hand grip on firearms, particularly emphasizing grip strength. However, it’s important to note that Fairbairn considered this approach more as one of the techniques rather than a preferred one in his time. Over time, as modern practical shooting has evolved, the emphasis on grip has become more pronounced, making two-handed shooting a more prevalent practice.

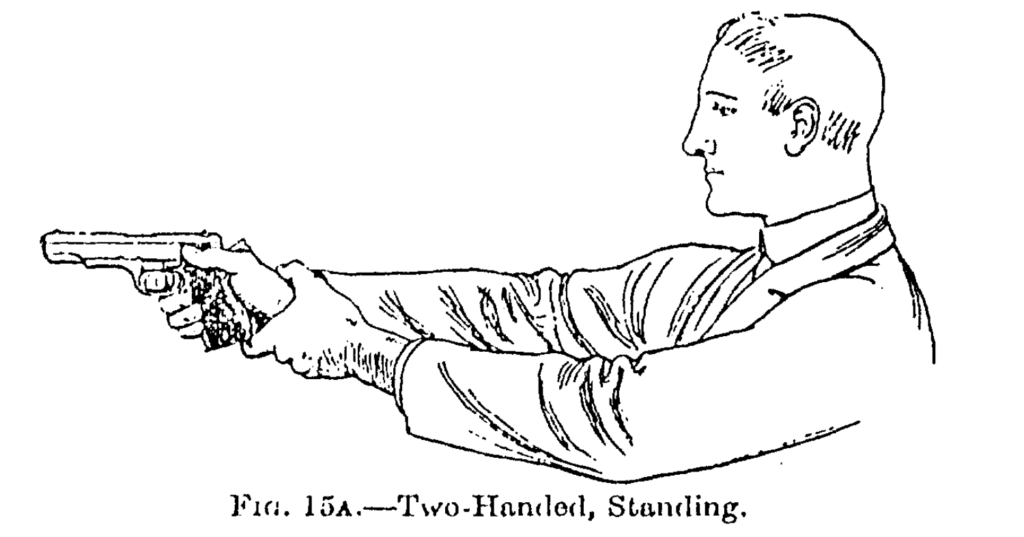

Figure 15a, depicting an alternate two-handed position, highlights Fairbairn’s perspective on the handgun as a “one-hand gun.” In this method, the support hand primarily aids in stabilizing the firearm while the primary hand operates it single-handedly. A comprehensive examination of his work reveals that Fairbairn viewed the pistol as a “one hand gun.”

In our contemporary context, shooting has evolved significantly. Advances in firearms equipment, optics, and training, along with the prevalence of weapon lights and body armor, have made fast and precise shooting with two hands more common and practical.

However, Fairbairn’s point about the “handgun” being designed for one-handed use remains valid. In its early days, the other hand of the shooter would likely have been occupied with holding reins or other duties. While two-handed shooting has become the norm in modern shooting, Fairbairn’s insights into one-handed use remind us of the pistol’s historical origins and intended functionality.

Practice Which Resembles Real Combat

Qualifications for recruits were based on hitting man-sized targets, emphasizing practicality over marksmanship badges. Fairbairn aimed to prepare recruits for duty, not merely award them accolades.

Dynamic training environments, with surprise targets and varied positions, were crucial in Fairbairn’s approach. Today, simulation training and stress-induced scenarios take this concept even further, providing a more realistic training experience.

Shooting Positions

Fairbairn held the belief that training should closely simulate real gunfighting scenarios. This entailed training in a wide range of positions and under various conditions, including different weather conditions, low-light environments, and even complete darkness. His approach emphasized the importance of preparing for the unpredictable nature of actual combat, ensuring that shooters could adapt and perform effectively regardless of the circumstances they might encounter in the field.

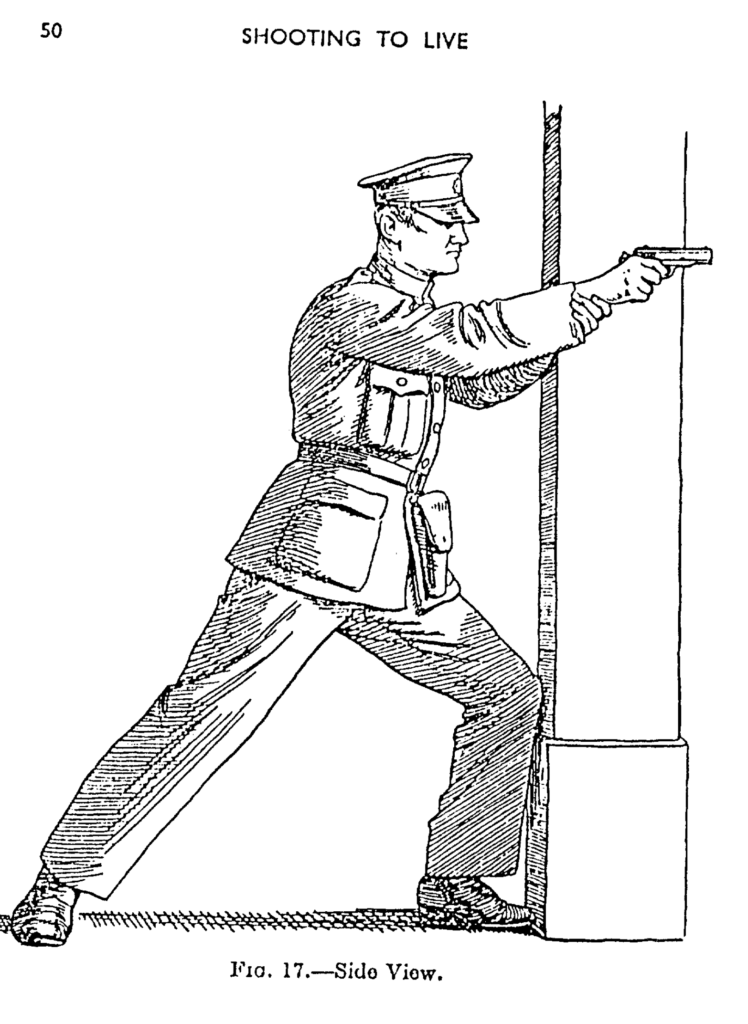

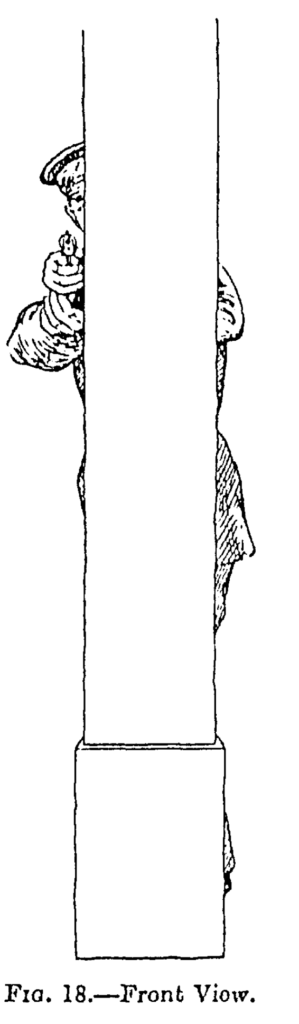

“Kind providence has endowed us all with a lively sense of self preservation and some of us with a sense of strategy as well. If our readers are in the latter class we need not remind them of the advantages of taking cover whenever possible. It is possible however that some of you have not thought of a telephone pole or electric light standard in that connection.

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

Fig17 will show you a side view of how to do it most conveniently, and fig 18 shows how and adversary will view the matter. Note in the former illustration that the position fo the foot, knees, and left forearm. The left knee and forearm are pressed against the pole, left hand is grasping the right wrist, thumb of right hand resting against the pole. Fig 18 also demonstrates that the almost perfect cover provided.”

Shooting to Live With the One-Hand Gun

Continuing the Legacy

In summary, William E. Fairbairn’s contributions to pistol shooting were groundbreaking. His insights, born from personal experiences and extensive analysis, forever changed the landscape of practical shooting. While some of his methods have evolved, his legacy as the father of practical shooting endures. His approach as an instructor was a data-driven. As a student of the handgun he put his life on the line daily in the laboratory of the Streets of Shanghai. He had a passion to share his knowledge with others, leaving a lasting impact on the world of combat shooting.

We continue to honor his legacy by following in his footsteps today, utilizing modern technologies such as body cams for reviewing and studying violent encounters, force-on-force training with simunition, and advanced simulators that recreate real-life decision-making with tangible consequences, like electric shock pain penalties.

These innovations allow us to follow in his footsteps and further build upon Fairbairn’s pioneering work in practical shooting.